An introduction to Partnership

Are you concerned about what’s going on in your life and our world?

Do you worry about what kind of future we face? Are you looking for a way forward?

Be part of the partnership movement.

“The struggle for our future is not between East and West or North and South, but everywhere between those who believe our only alternatives are dominating or being dominated and those working for partnership relations of mutual respect, accountability, and caring.”

-Riane Eisler’s Cultural Transformation Course

Contents

• Changing lives

• What partnership means for you

• Personal & cultural transformation

• Our history, our future

• Partnership politics – from intimate to international

• Sex and the politics of the body

• Toward a new economics

• Women, men, and economic development

• From poverty to partnership

• Changing measures of economic health

• Four cornerstones for a world of partnership and peace

• Partnership education

• Center for Partnership Systems

Changing Lives

“I want to thank you for being my teacher and mentor. Your exposition of the dominator and partnership organizational models within the deep context of the human experience has had a foundational influence on my own work, particularly in writing The Great Turning: From Empire to Earth Community. Thank you also for providing a model for us all at this time when our society needs elders serving in the roles of teacher, mentor, and wisdom keeper as never before.”

David Korten, Co-founder, Positive Futures Network

“From your breakthrough statements in The Chalice and The Blade to your more recent The Power of Partnership and The Real Wealth of Nations, your writings have inspired my thinking and impacted The Hunger Project’s work on gender. You are a clear and compelling voice for the empowerment of women and the wisdom of true partnership in our world.”

Joan Holmes, President, The Hunger Project

“You are an inspiration to women from all racial backgrounds, to poor and wealthy women alike, to life loving men. As a Mexican ARTivist I am very proud to have read and distributed your literature.”

Silvia Parra

What partnership means for you

Many of us are hungry for transformative change – personal, social, economic. But as Einstein said, we can’t solve problems with the same thinking that created them. Let’s start by thinking outside the old boxes of capitalism, socialism, right, left, religious, secular, Eastern, Western because societies in all these categories have been oppressive, violent, and unjust. None of them help us answer the most urgent question for our future: what social conditions support the expression of our great human capacities for consciousness, caring, and creativity – or for insensitivity, cruelty, and destructiveness?

The new categories of partnership system and domination system answers this question. They reveal patterns that are invisible through the lenses of older social categories.

Personal and cultural transformation

Can we build a world where our great potentials for consciousness, caring, and creativity are realized? What would this more equitable, less violent world look like? How can we build it?

These questions animated my research over the past four decades. They arose very early in my life, when my parents and I narrowly escaped from Nazi Europe. Had we not been able to flee my native Vienna and later find refuge in Cuba, we would almost certainly have been killed in the Holocaust, as happened to most of my extended family.

As I grew up in the industrial slums of Havana, I didn’t realize that studying social systems would become my life’s work. By the time I did, it was clear that our present course is not sustainable. In our time of nuclear and biological weapons, violence to settle international disputes can be disastrous. So can our “conquest of nature” when advanced technologies are causing environmental damage of unprecedented magnitude.

I saw that a grim future awaits my children – and all of us – unless there is transformative cultural change. But the issue addressed by my multi-disciplinary, cross-cultural, historical study of human societies is: transformation from what to what?

From old to new thinking

Not so long ago, many people thought that shifting from capitalism to communism would bring a more just, less violent society. But the communist revolutions in Russia and China brought further violence and injustice. Today many people believe that capitalism and democratic elections are the solution. But capitalism has not brought peace or equity: Hitler was democratically elected, and elections following the Arab Spring led to repressive Islamist regimes. Others argue that returning to pre-scientific Western times or replacing Western secularism, science, and technology with Eastern religions will cure our world’s ills. They ignore that the religious Middle Ages were brutally violent and repressive, that Eastern religions have helped perpetuate inequality and oppression, and that today’s fundamentalist religious cultures, both Eastern and Western, are behind some of our planet’s most serious problems.

All these approaches are based on old thinking. As long as we look at societies from the perspective of conventional categories such as capitalist vs. socialist, Eastern vs. Western, religious vs. secular, or technologically developed vs. undeveloped, we cannot effect real cultural transformation. Indeed, history amply shows that societies in every one of these categories can be, and have been, repressive, unjust, and violent.

This is why my re-examination of social systems transcends old categories. It uses a new method of analysis (the study of relational dynamics) that draws from a larger data base than conventional studies. It looks at a much larger, holistic picture that includes the whole of humanity, both its female and male halves; the whole of our lives, not only politics and economics but where we all live, in our family and other intimate relations; and the whole of our history, including the thousands of years we call prehistory.

Looking at this more complete picture makes it possible to see interactive relationships or configurations that are not visible otherwise. There were no names for these social configurations, so I called one the domination system and the other the partnership system.

Once we understand these configurations, it becomes clear that the real struggle for our future is not religious vs. secular, East vs. West, South vs. North, right vs. left, etc. If you think about it, societies in all these categories were, and are, repressive, violent, and unjust.

The real struggle is within societies in every one of these categories, between people who want to move to a more caring and equitable world and those you still believe insensitivity, cruelty, and destructiveness – and all the misery they lead to – are “just human nature” – the inevitable result of original sin or selfish genes.

From Domination to Partnership

Before Newton identified gravity, apples fell off trees all the time but people had no name or explanation for what was happening. The partnership and domination systems not only give us names for different ways of relating but also explain what lies behind these differences.

We’re all familiar with relations of domination and submission from our own lives. We know the pain, fear, and tension of relations based on coercion and accommodation, of jockeying for control, of trying to manipulate and cajole when we are unable to express our real feelings and needs, of the tug of war for that illusory moment of power rather than powerlessness, of our unfulfilled yearning for caring and mutuality, of all the misery, suffering, and lost lives and potentials that come from these kinds of relations.

Most of us have also, at least intermittently, experienced another way of being, one where we feel safe and seen for who we truly are, where our essential humanity and that of others shines through, perhaps only for a little while, lifting our hearts and spirits, enfolding us in a sense that the world can after all be right, that we are valued and valuable.

Our human yearning for caring connections, for peace rather than war, for equality rather than inequality, for freedom rather than oppression, can be seen as part of our genetic equipment. The degree to which this yearning can be realized is not a matter of changing our genes, but of building partnership social structures and beliefs.

Two different kinds of relationships

In the domination system, somebody has to be on top and somebody has to be on the bottom. People learn, starting in early childhood, to obey orders without question. They learn to carry a harsh voice in their heads telling them they’re no good, they don’t deserve love, they need to be punished. Families and societies are based on control that is explicitly or implicitly backed up by guilt, fear, and force. The world is divided into in-groups and out-groups, with those who are different seen as enemies to be conquered or destroyed.

In contrast, the partnership system supports mutually respectful and caring relations. Because there is no need to maintain rigid rankings of control, there is also no built-in need for abuse and violence. Partnership relations free our innate capacity to feel joy, to play. They enable us to grow mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. This is true for individuals, families, and whole societies. Conflict is an opportunity to learn and to be creative, and power is exercised in ways that empower rather than disempower others.

Here’s an example. Do you remember how the father treated his children in the movie The Sound of Music? When Baron von Trapp (Christopher Plummer) blows his whistle and his children line up in front of him, stiff as boards, you see the domination system in action. When the new nanny (Julie Andrews) comes into the picture and the children relax, enjoy themselves, and learn to trust themselves and each other, you see the partnership system in action. When von Trapp becomes much happier and closer to his children, you see what happens as we begin to shift from domination to partnership.

Our history, our future

The last three hundred years have seen a strong movement toward partnership. One tradition of domination after another has been challenged – from the rule of despotic kings and male dominance to economic oppression and child abuse.

But this forward movement has been fiercely resisted, and punctuated by periodic regressions. That is the bad news.

The good news is that we do not have to start from square one. Though we still have a long way to go, in bits and pieces the shift from domination to partnership is underway.

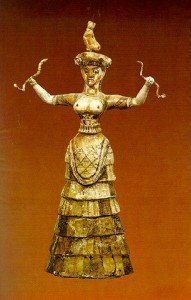

There is also strong evidence from archeology and the study of myth that the original direction in the mainstream of our cultural evolution was in a partnership direction. So much that today may seem new and even radical, such as gender equality and a more peaceful way of life, has ancient roots going back thousands of years, before the cultural shift toward domination about 5000 years ago.

During much of recorded history, rankings of domination – man over man, man over woman, race over race, nation over nation, and humans over nature – have been the norm. But in our time of nuclear and biological weapons and high technology in service of the once hallowed “conquest of nature, “high technology guided by an ethos of domination could take us to an evolutionary dead end.

In sum, the struggle for our future is not between East and West, North and South, religion or secularism, capitalism or socialism, but within all these. It is the struggle between those who cling to patterns of domination and those working for a more equitable partnership world.

Each one of us can contribute to the partnership movement. We can change by example, education, and advocacy. We can shift our relations from domination to partnership – starting with our day-to-day relations all the way to how we relate to our mother earth.

Two contrasting configurations

Societies adhering closely to the Domination system have the following core configuration:

- top-down authoritarian control in both the family and state or tribe

- the subordination of the female half of humanity to the male half, and with this, the

devaluation of caring, nonviolence and other stereotypically “soft” values in women and

men a high degree of institutionalized or built-in fear, coercion, and violence

Societies adhering closely to the Partnership system have a different core configuration:

- A more democratic organization in both the family and state or tribe

- the male and female halves of humanity are equally valued and “soft” or stereotypically feminine traits and activities such as caring and nonviolence are highly regarded in both women and men

- a low degree of institutionalized or built-in fear, coercion, and violence

The evolution of societies from prehistory to the present reflects the underlying tension between the configurations of the partnership and domination systems as two basic alternatives. These two systems structure our relations with one another and our natural environment and represent opposite ends of a spectrum of cultural possibilities.

We humans have the capacity for both consciousness, caring, and creativity as well as for insensitivity, cruelty, and destructiveness. The question is what social conditions support the expression one or the other set of these human capacities. To answer that question we have to transcend old categories, and look at a less fragmented picture.

This picture is provided by the two contrasting configurations of the partnership system and the domination system, which include the social construction of two key social components ignored, or at best glossed over in conventional discourse:

• The social construction of the relations between the female and male halves of humanity

• The construction of the relations between parents and children

The reason we must look at these relations is something we have long known from psychology and now also know from neuroscience. This is that it is by experiencing and observing these relations that children learn, before their brains are fully formed, what is considered moral or immoral, desirable of undesirable, and even possible or impossible.

The importance of parent-child and gender relations in these two social configurations cannot be overemphasized – especially they are ignored in conventional theories about society.

To give just one example of the interactive dynamics of domination systems, people raised in families with the domination perspective—families where they learn that the adults on whom they depend for their survival may not be contradicted—tend to have a hard time contradicting what their “superiors” tell them, even when they are adults. They therefore tend to:

• Find it difficult to question, much less challenge, powerful economic interests on whom they feel dependent

• Have difficulty looking at the long-range future

• Place emphasis on the short-term bottom line because they’re stuck in a defensive mode of protecting themselves and what they have

• Have trouble dealing with change (Eisler, The Power of Partnership, 2002, p. 161)

Partnership politics – from intimate to international

A Progressive Family Policy Agenda

It is time for progressives to reframe the political conversation about family values and have an integrated progressive family policy agenda.

Progressives have ceded the meaning of family life to regressives, who recognize the foundational importance of family and other intimate relations in the establishment of social values and political and economic structures. Family relations affect how people think and act. They affect how people vote and govern, and whether the policies they support are just and genuinely democratic, or punitive, violent, and oppressive.

Regressives have successfully pushed our culture back by insisting that a male-dominated, top-down structure of family is the only desirable one. U.S. fundamentalists stress the “headship” of the father in the family, with women and children subordinate. So successful were their efforts to establish this model that in 1992, when Americans were asked if the “father of the family is master of the house,” just 42% said yes. By 2004 the percentage had risen to 52% — compared to only one third of Canadians and 20% of Europeans agreeing with this “traditional value.”

Slogans like “traditional values” have often marketed a family where fathers make the rules and harshly punish disobedience – the kind of family that prepares people to defer to “strong” leaders who brook no dissent and use force to impose their will. This is the fundamentalist theocratic model of society for our future — and we see the horrors it brings by looking at Eastern fundamentalist regimes.

What is urgently needed is an integrated progressive family policy agenda that redefines “family,” “values,” and “morality” in ways based on partnership, mutual respect, and caring rather than domination, top-down control, and coercion.

Progressive candidates can start by changing the terms of the debate:

1. Replace the regressive “family values” agenda with an agenda that “values families.”

2. Introduce the term “real wealth of our nation” – people and nature.

3. Link family-friendly business and government policies with a strong competitive workforce.

4. Link children’s health, education, and welfare and the future of our economy and society.

Sex and the Politics of the Body

Excerpts from Sacred Pleasure

Selected excerpts from Riane Eisler’s book Sacred Pleasure: Sex, Myth, and the Politics of the Body (1995).

“Could it be that the yearning of so many women and men for sex as something beautiful and magical is our long repressed impulse toward a more spiritual, and at the same time more intensely passionate, way of expressing sex and love?

Candles, music, flowers, and wine – these we all know are the stuff of romance, of sex and of love. But candles, flowers, music, and wine are also the stuff of religious ritual, of our most sacred rites. Why is there this striking, though seldom noted, commonality? Is it just accidental that passion is the word we use for both sexual and mystical experiences? Or is there here some long forgotten but still powerful connection? Could it be that the yearning of so many women and men for sex as something beautiful and magical is our long repressed impulse toward a more spiritual, and at the same time more intensely passionate, way of expressing sex and love?

Because we have been taught to think of sex as sinful, dirty, titillating, or prurient, the possibility that sex could be spiritual, much less sacred, may seem shocking. . .Yet the evidence is compelling that for many thousands of years – much longer than the thirty to fifty centuries we call recorded history – this was the case.

You can obtain Sacred Pleasure online here.

Toward a new economics

The real wealth of a nation is not financial. This became painfully obvious with the melting into thin air of credit swaps and derivatives during the “Great Recession.” Indeed, you can see the ephemeral nature of financial riches every day, as stock prices, home prices, and other financial valuations seesaw up and down.

A nation’s real wealth consists of the contributions of people and of nature. Therefore, we

need what we have not had—economic measurements, policies, and practices that give visibility and adequate value to the most important human work: the work of caring for people, starting in early childhood, and caring for our natural environment.

Without caring and caregiving, none of us would be here. There would be no households, no workforce, no economy, nothing. Especially now, when flexible, creative people who can work in teams and think in long-term ways are essential for economic success, it can be argued that the caring activities still generally categorized as “reproductive work” are actually the most productive activities of all. Similarly, caring for our natural environment is today a prerequisite not only for sustainability, but also for humanity’s future survival.

Yet despite all this, most current economic discussions do not mention caring and caregiving. Nor is the value of the work of caring in households included in current economic measurements.

It does not have to be this way. Indeed, the social and economic dislocations inherent in the current shift from the industrial to the post-industrial era offer us an unprecedented opportunity to reexamine and restructure economic theory and practice.

Availing ourselves of this opportunity is essential if we are to move to a more equitable, sustainable, and caring future. We know today, from both psychology and neuroscience, that whether or not people are cared for directly impacts human development, health, and life quality.

Caring economics and real wealth

Some people in the U.S. think that the next generation will be the first to NOT surpass the current generation’s wealth–and by that they mean the accumulation of money, possessions, and property. However, we have to ask, were we really wealthy? Financial wealth can disappear, like the credit swaps and derivatives did, in a matter of seconds.

What many are discovering is that the current financial wealth system often comes at the expense of our children, our families, communities, and the planet. They are waking up to a new definition of wealth. We need an economic system that make it possible to have healthy food, good housing, enriching schools, natural and recreational space, and a sense of community.

Study after study shows that what people truly find most valuable are relationships, meaning, service, and a sense of purpose. But the current economic system does not support or give value to caring for people, starting in early childhood, and caring for our Mother Earth. We can, and must, change this! We can have an economic system that meets everyone’s material needs and makes it possible for us to have time and energy for our children, our communities, and ourselves.

Women, Men, and Economic Development

Studies demonstrate the connection between the status of women on the one hand and a nation’s quality of life and economic success on the other. A pioneering study was Women, Men, and the Global Quality of Life conducted by the Center for Partnership Studies (CPS) in 1995. Using data from 89 nations, it compared the status of women with measures of quality of life (such as infant mortality, human rights ratings, and environmental ratings) and showed that in significant respects, the status of women can be a better predictor of quality of life than GDP (Eisler, Loye, & Norgaard, 1995).

Since then, other studies have verified the relationship between the status of women, a society’s values, and its overall quality of life and economic success. Based on data from 65 societies representing 80% of the world’s population, the World Values Survey (Inglehart, Norris, & Welzel, 2002) is the largest international survey of how attitudes correlate with economic development and political structure. When for the first time this survey focused attention on attitudes about gender, it found a strong relationship between the level of support for gender equality and a society’s level of political rights, civil liberties, and

quality of life.

More recently, in the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Reports, researchers Hausmann, Tyson, and Zahedi, (2011) showed that the nations with the lowest gender gaps (such as Norway, Sweden, and Finland) are also regularly in the highest ranks of the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Reports.

The simple fact that women are half of humanity is a reason for the correlation between the status of women and national economic success and quality of life. But the reasons go much deeper, to the still largely unrecognized interconnected cultural, social, and economic dynamics inherent in domination systems or partnership systems.

In addition to the connection between a higher status of women and values and policies that support caring for people, there are a myriad other factors, including yet another matter ignored in conventional economic analyses: how resources are distributed not only within nations, but within households.

Eisler and other scholars call this intra-household economics (Eisler, 2007; Jain & Banerjee, 1985), and it is once again directly related to the status of women in a society. Empirical evidence across diverse cultures and income groups shows that in cultures where women are rigidly subordinated, the distribution of household resources tends to be skewed in ways that fail to invest in children’s well-being, health, and development. Studies also show that in these domination-oriented cultures, women have a higher propensity than men to spend on goods that benefit children and enhance their capacities. For example, in “Intra-Household Resource Allocation,” Duncan Thomas (1990) found that $1 in the hands of a Brazilian woman had the same effect on child survival as $18 in the hands of a man. Similarly, Bruce and Lloyd (1997) found that in Guatemala an additional $11.40 per month in a mother’s hands would result in the same weight gain in a young child as an additional $166 earned by the father.

Of course, even in rigidly male-dominated cultures there are men who give primary importance to meeting their families’ needs. However, the socialization of men in such cultures teaches them to believe it is their prerogative to use their wages for non-family purposes, including drinking, smoking, and gambling (and that when women complain, they are nagging and controlling).

The negative effects of the subordination of females to males on intrahousehold resources distribution go even further. In some world regions, parents (both mothers and fathers) often deny girls access to education, give them less health care, and even feed girls less than boys. Obviously, these practices have terrible health consequences for girls and women. Indeed, these practices are horrendous human rights violations that not only stunt girls’ development, but all too often cause their death. But giving less food to girls and women also adversely impacts the development of boys, as children of malnourished women are often born with poor health and below-par brain development (Eisler, 1987b). In short, this gender-based nutritional and health care discrimination robs all children, male and female, of their potential for optimal development.

This in turn affects children’s and later adults’ abilities to adapt to new conditions, tolerate frustration, and avoid using violence—all of which impede solutions to chronic hunger, poverty, and armed conflict, as well as the chances for a more humane, prosperous, and peaceful world for all.

From Poverty to Partnership

There is no realistic way to end poverty without taking into account the fact that women represent a disproportionate percentage of the poor worldwide.

• According to some estimates, 70% of those who live in absolute poverty—starvation or near starvation—are female (UN Women, n.d.).

• Even in the rich United States, woman-headed families are the lowest tier of the economic hierarchy (UN Women, n.d.).

• According to the United States Census Bureau, the poverty rate of women over 65 is double that of men the same age.

This high female poverty rate is not only due to wage discrimination in the market economy; it is largely due to the fact that these women are (or were for much of their lives) either full- or part-time caregivers of children or other family members. Yet because they did this essential work without pay or later Social Security or pensions, they are condemned to an old age living in poverty.

This, however, is not inevitable. It is a matter of social policies.

Demonstrating the importance of changing policies are the low poverty rates of the nations that orient more to the partnership side of the continuum, such as Sweden, Norway, and Finland. Here women and stereotypically feminine values have higher status. Not only that, Sweden has a high woman-headed household rate, yet these families are not poor. Women, who are 40 percent of the legislatures, tend to support more caring policies as a group. As the status of women rises, men no longer find is such a threat to their status to embrace more stereotypically feminine values and behaviors.

But while the Global Women’s Movement is beginning to gain momentum it is still much too slow and it is still fiercely opposed in some cultures and subcultures – all too often violently. And, as in the push by so-called religious fundamentalists worldwide to return women to their subordinate, “traditional” place in male controlled families, the resistance to raising women’s status is fiercest among those who also want to impose repressive national regimes and gain global control through “holy wars.” In other words, it is key to the domination system they seek to impose.

Changing Measures of Economic Health

Current economic measures such as Gross Domestic Product (GDP) fail to give economic value to the most essential human work: caring for people and nature.

A 2004 Swiss government report showed that if the unpaid “caring” household work still primarily performed by women were included, it would comprise 40% of the reported Swiss GDP (Schiess and Schön-Bühlmann, 2004). Unfortunately satellite accounts do not get the publicity of economic measures such as GDP. But they are a start in the right direction.

Reports by nongovernmental organizations also show the enormous value of the work of care. A recent example is Counting on Care Work in Australia (Hoenig & Page, 2012), a comprehensive quantification of the Australian care sector, paid and unpaid. The study used both replacement value (which reflects the low pay of care work in the market) and opportunity cost (which yields a higher value on average, measuring opportunity cost for individuals who perform unpaid care instead of entering the paid work force). The study found that the care sector in Australia was worth an estimated $762.5 billion in 2009-10. Of this total, $112.4 billion was for paid care and $650.1 billion was for unpaid care work.

The latter was the equivalent of no less than 50.6% of GDP. Another key finding was that women contributed the majority of this unpaid care, similar to other world regions (Hoenig, & Page, 2012).

The Australian report pointed out that care work is a “public good” and that, given its profound implications for a nation’s overall well being, government intervention in the form of public policy and funding is required to ensure that appropriate levels of care are available (Hoenig and Page, 2012).

While data showing the huge economic value of care work continue to accumulate, they are still given scant attention by academics, media, policy makers, and the public. A major reason for this neglect is that the information does not fit into the old economic paradigms or the old ways of measuring economic health such as GDP. This is why the development of new measures of economic health such as the Social Wealth Economic Indicators being developed by the Center for Partnership Studies (CPS) are so important.

We must show our nation’s policymakers the necessity for enacting more caring policies. There is a connection between the status of women and whether caring and caregiving are valued. Therefore, we must also show policymakers the necessity of raising the status of women worldwide.

The unsustainable nature of current ways of economic thinking and planning is further demonstrated by the fact that a growing number of jobs—not only in manufacturing but also in service industries, from receptionists to middle management—are being taken over by automation and robotics (Associated Press, 2013). This irreversible trend, which will further accelerate with the development and use of artificial intelligence and nanotechnology, makes it even more urgent that we find alternatives to economic systems primarily driven by consumer spending.

Four cornerstones for a world of partnership and peace

In this article for the Kosmos Journal, Eisler lays out four interventions that provide the foundations for shifting from domination to partnership.

Partnership education

As detailed in Tomorrow’s Children: A Blueprint for Partnership Education in the 21st Century, educators need to keep in mind — and teach our students — to broaden our understanding of events by going beyond conventional political debates about right versus left, religious versus secular, Eastern or Western, or conservative versus liberal. Once students understand the dynamics of the tension between the partnership and domination systems as two basic human possibilities, they can go beyond surfaces. They can see the patterns that underlie seemingly unrelated currents and crosscurrents in our world — and be better equipped to live good lives and intervene in shaping their future. Read/ Buy Tomorrow’s Children.

Study and action groups

You can form your own study and action group, using the following resources:

Real Wealth of Nations study group

To create a caring economics, start a Study and Action Group on The Real Wealth of Nations.

Power of Partnership study group

To build partnership human and environmental relations, The Power of Partnership: Seven Relationships That Will Change Your Life is a key how-to book.

To ensure long-term environmental sustainability, use the action steps in The Power of Partnership and The Real Wealth of Nations: Creating a Caring Economics.

The Chalice and the Blade study group

To start a study group on The Chalice and The Blade: Our History, Our Future and/or Sacred Pleasure: Sex, Myth and the Politics of the Body, use The Partnership Way: New Tools for Living and Learning, a workbook for facilitators by Riane Eisler and David Loye

Tomorrow’s Children study group

To build partnership education, use Tomorrow’s Children: A Blueprint for Partnership Education for the 21st Century

Academic Study groups

Partnership Studies Group Learn more about building partnership communities from this successful Partnership Studies Group at the University of Udine, Italy.

ALL-Associazione Laureati in Lingue is an active group of scholars at the University of Udine who are researching and advocating for partnership.

Center for Partnership Systems

The Center for Partnership Systems is a public service organization dedicated to cultural transformation from domination to partnership systems. Founded in 1987, CPS has worked with thousands of individuals and organizations to change consciousness, promote positive personal action, encourage social advocacy, and influence policy.

CPS uses research, education, and advocacy to reframe thinking and social policy to achieve gender and racial equity, human rights, social justice, and building a successful economy. The Center for Partnership Studies is an internationally-recognized thought leader in strategies to create a “partnership culture” of human rights and equity.

For more details about CPS’s work and latest accomplishments, please visit us online at the Center For Partnership Systems website.

Breaking Cycles of Violence: The Spiritual Alliance to Stop Intimate Violence (SAIV)

SAIV was co-founded by Dr. Riane Eisler and Nobel Peace Laureate Betty Williams in 2004, as a project of the Center for Partnership Studies (www.CenterForPartnership.org). The SAIV Global Council provides a moral voice to engage spiritual leaders, policy makers, and activists to advocate for increased resources to end the global pandemic of violence against women and children.

SAIV invites contributions from the public and faith communities for engagement to “break cycles of violence in families – and the families of nations.” Resources at www.saiv.org include the new Domestic Violence and Religion special collection of the National Resource Center on Domestic Violence, Dr. Eisler’s videos for teaching, discussion about moving from domination to partnership systems, the “Caring and Connected Parenting Guide” by Licia Rando endorsed by Nobel Peace Prize Laureates Desmond Tutu and Betty Williams, pediatrician T. Berry Brazelton, and much more.

SAIV Global Council

Africa

Ela Gandhi

Jane Goodall

Molly Melching

Emilia Muchawa

Netsai Mushonga

Millicent Obaso

Archbishop Desmond Tutu

Asia

Durre Ahmed

A.T. Ariyaratne

Tenzin Choegyal Ngari Rinpoche

Prof. Chung Hyun-kyung

Kalon Rinchen Khando

Europe

Satish Kumar

Marshall B. Rosenberg

Betty Williams

Harvey Cox

Richard Deats

Riane Eisler

Joan Holmes

Barbara Marx Hubbard

Jim Kenney

Irfan Ahmad Khan

Frances Kissling

John Robbins

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi

Bill Schulz

Sunita Viswanath

Middle East

Dr. Saleha Abedin

Prince El Hassan bin Talal

Her Majesty Queen Noor

The Americas

Lauren Artress

Liliane Kshensky Baxter

John A. Buehrens

Raffi Cavoukian

Janet Chisholm

Deepak Chopra

Joan Chittister, OSB

Research Findings

“Human Evolution is now at a crossroads. Stripped to its essentials, the central human task is how to organize society to promote the survival of our species and the development of our unique potentials. A partnership society offers us a viable alternative.” — Riane Eisler, The Chalice and The Blade